In most popular retellings of the stories of Robin Hood from the 20th & 21st centuries our hero has been a nobleman, or at least, as in Ridley Scott’s case, pretending to be one. He has either been Robert the Earl of Huntingdon, or Sir Robin of Locksley. Now because Robin Hood is a folk hero and the idea of who he is and what he does, has changed over time and with each poem, ballad, story, play, or film that he appears in. So, it would be a bit gauche of me to say definitively who Robin Hood is or what he should be. However, I am going to look over the way Robin Hood has been a bit of a social climber (especially for a fictional character) over the last 500 years or so; and with this surprising social mobility how his motives and actions change. So: Robin Hood. He steals from the rich and gives to the poor. He battles against the evil Sherriff of Nottingham, exposes Prince John, saves Maid Marian, gets knocked into the river by Little John and saves the kingdom for Good King Richard. But also, Robin Hood, much like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. As a fairly amorphous figure, with a large corpus of literature to draw from it is easy to project whatever values you desire on to him. [1]

Robin of the earliest poems and ballads is a man very much of the times written, a time when violent acts could be seen as either justified or wrongdoing depending on local factors of superiority, or favour with the King.[2] The earliest attempt at a single overarching narrative for Robin Hood is A Geste of Robyn Hood, a sort of epic poem, which is a series of ballads sewn together. The extant literary sources come from the 16th century on, but these are probably based on, or are altered versions of older stories.[3] In the Geste and the other early poems what makes Robin almost unique is his relatively humble social standing. [4]There are for instance many contemporaneous poems about Hereward the Wake, many of which are now lost to us;[5] Hereward, ‘the lineal ancestor of the later English outlaws’,[6] is a member of the nobility. The outlaw status is temporary for these men like Hereward and Gamelyn, they only turn outlaw with their dispossession of land and standing.[7] Their removal from society. [8]

In Eric Hobsbawm’s model of the ‘social bandit’, Robin Hood is the archetypical Noble Robber.[9] The idea of social banditry a form of class struggle, where robbery is supported by the working and lower classes.

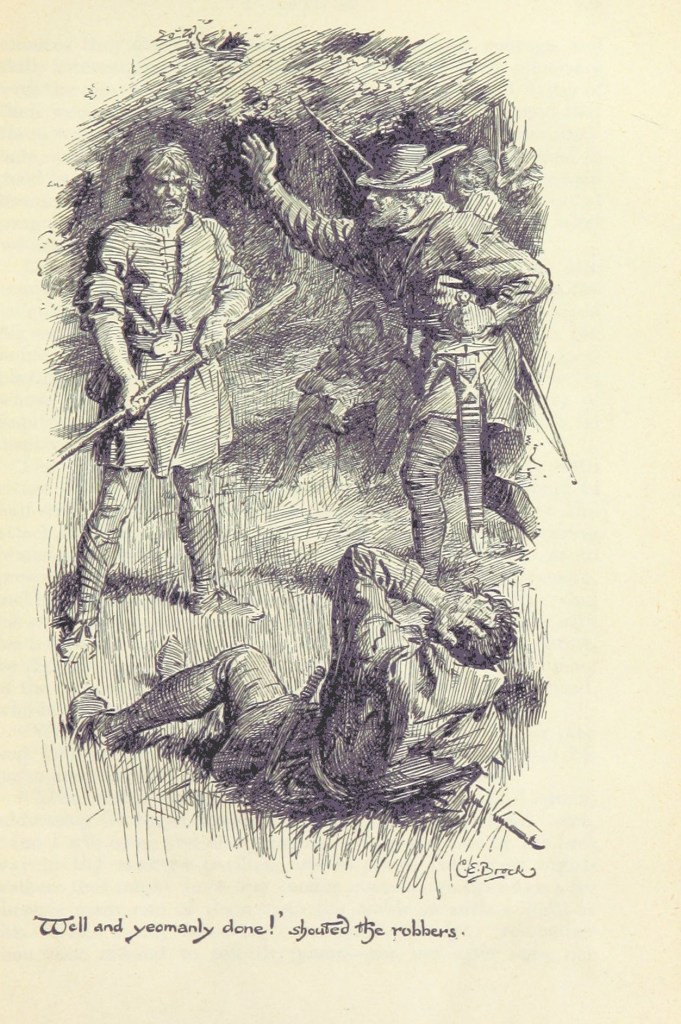

The malleability of Robin Hood as a character comes down to the simplicity of the stories, which allow the teller to change and adapt the stories to tailor them to their audience, introducing new characters, and changing emphasis.[10] The early ballads often began with an address to the audience, and often these are explicitly addressing the yeomanry and the gentry.[11] Hobsbawm argued that the bandit as a social hero belongs entirely to the peasantry but concedes that as a cultural symbol, he holds a much wider appeal.[12] This is indeed the case for Robin, as he does not come from the great masses of the people, but is explicitly from the yeomanry,[13] and as such is a freeman who would have owned property in his own right, not a villain or crofter tied to a particular lord or holding. So already, even in the earliest sources, Robin’s social position only represents a small part of the population.

Over time in the ballads and stories he loses his anti-clerical, anti-authority stance for a more broad and smooth anti-injustice outlook. Robin’s stories become set at a specific time and space, Nottingham and Sherwood during the 3rd Crusade. He is looking to restore the rightful rule of Good King Richard and resist the perfidy and rapaciousness of the evil Prince John and his cronies. In most modern incarnations he fits more into an idea of ‘The Gentleman Bandit’, like Hereward, or the popular image of 18th century highwaymen like Dick Turpin. Since Anthony Munday’s two plays, The Downfall and The Death of Robert, Earl of Huntington, Robin certainly fits into this image. Munday, a bit of a social climber himself as the son of a draper,[14] recognised the difference in his representation of Robin Hood, and acknowledges the unusual step of granting peerage to his hero early in the The Downfall (1598):

This youth that leads yon virgin by the hand

(As doth the Sunne, the morning richly clad)

Is our Earle Robert, or your Robin Hoode,[15]

Munday takes his step in this not from the ballads and May Day games, but from historical chronicles, such as Richard Grafton’s Chronicle at Large in 1568.[16] Grafton is the earliest to suggest that Robin is from the nobility. Munday’s play both elevates Robin from his traditional local enemies, the sheriff and the abbot, to the court, and removes his political teeth so that he ‘[becomes] depoliticised and personalised, opposed only to noblemen who were personally treacherous to him.’[17] Following on from Munday’s successes Robin Hood made an appearance in at least 5 plays in the first 3 years of the 17th century,[18] into including Shakespeare’s As You Like It, which while not a Robin Hood play explicitly, certainly takes many cues from Munday’s works.[19]

In Ivanhoe, by Sir Walter Scott Robin Hood plays a secondary role to the titular character but returns to his yeoman status. Scott is drawing a dichotomy between the bluff, honest Saxon and the dissembling Norman (a difference which we will see again when we turn to look at film, though with Robin back above the salt).[20]

Bibliography

DeAngelo, Jeremy. Outlawry, Liminality, and Sanctity in the Early Medieval North Atlantic. Amsterdam, 2019.

Doniger, Wendy. ‘Female Bandits? What next!’ in The London Review of Books Vol. 26, No. 14 (2004).

Firth Green, Richard. ‘Violence in the Early Robin Hood Poems in A Great Effusion of Blood’?: Interpreting Medieval Violence, edited by Mark D. Meyerson, Daniel Thiery, & Oren Falk, pp. 268-286. Toronto, 2004.

Gerritsen, Willem P. & van Melle, Anthony G. A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes. Woodbridge, 1998.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Bandits. London, 1969.

Holt, J.C. Robin Hood. London, 1982.

Kaufman, Alexander L. ‘A Desire for Origins: The Marginal Robin Hood in the Later Ballads’ Medievalism on the Margins, edited by Karl Fugelso, Vincent Ferré & Alicia C. Montoya, pp. 51-62. Woodbridge, 2015.

Nicholl, Charles. The Reckoning. London, 1992.

Philips, Helen. Robin Hood: Medieval and Post Medieval. Dublin, 2005.

Scattergood, John. Reading the Past: Essays on Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Dublin, 1996.

Seal, Graham. Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History. London, 2011.

Skura, Meredith. ‘Anthony Munday’s “Gentrification” of Robin Hood’ in English Literary Renaissance

Vol. 33, No. 2 (Spring, 2003), pp. 155-180.

Ballads of Robin Hood and other Outlaws, by Frank Sidgwick. London, 1912. Accessed from Project Gutenburg http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28744/28744-h/28744-h.htm

[1] Douglas Gray, ‘Everybody’s Robin Hood’ in Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval, edited by Helen Phillips (Dublin, 2005), p. 21.

[2] J.C. Holt, Robin Hood, (London, 1982), p. 6.

[3]Willem P. Gerritsen & Anthony G. Melle, A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes (Woodbridge, 1998), p. 227.

[4] Timothy S. Jones, ‘Oublïé ai cevalerie’: Tristan, Malory and the outlaw-knight’ in Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval, p. 79.

[5] Gray, ‘Everybody’s Robin Hood’, p. 33.

[6] Maurice Keen, The Outlaws of Medieval Legend, quoted in Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History by Graham Seal, (London, 2011), p. 38.

[7] Jeremy DeAngelo, Outlawry, Liminality, and Sanctity in the Early Medieval North Atlantic, (Amsterdam 2019), p. 199.

[8] A poem exists where Gamelyn or rather Gandeleyn refers to himself and takes on a similar role to Little John, found in Frank Sidgwick’s Ballads of Robin Hood and Other Bandits, p. 92.

[9] Eric Hobsbawm, Bandits (London, 1969), p. 23.

[10] Holt, Robin Hood, 12.

[11] Holt, Robin Hood, 105.

[12] Hobsbawm, Bandits, p. 141.

[13] Gerritsen & van Melle, A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes p. 228.

[14] Charles Nicholl, The Reckoning (London 1992), p. 174

[15] Anthony Munday, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntingdon, ll 86-88.

[16] Liz Oakley-Brown ‘Anthony Munday’s Huntingdon Plays’ in

[17] Wendy Doniger, ‘Female Bandits? What next’ The London Review of Books 26, no. 14 (2004).

[18] Meredith Skura, ‘Anthony Munday’s “Gentrification” of Robin Hood’ Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval, p. 113.

[19] Nicholl, The Reckoning, p. 72.

[20] It would be overly long, or much to curt to put it here but I do want to discuss Robin Hood’s role and class perception on the silver screen, so I will hopefully return to this at some point in the future.