A study of the course of education in Ireland, both in the history of the modern independent state and beforehand under British administration, shows a change in the priority of policy and a gradual shift, in fits and spurts, from a curriculum and organisation lead by church authorities to one with a greater degree of involvement by the state in a secular position. This essay will explore the historical course of educational policy in Ireland both as an independent state and before and will examine the collegial relationship between the church and state with respect to educational policy that has been the tenor in education until very recent history.

In one of the earliest forms of tension between Church and state over educational policy, in 1791 a commission into the state of education in Ireland criticised the running of schools by Protestant clergy and proposed that the running of them should be handed over to local laymen, including Catholics (Fleming, 2017, p. 27). In this way though non-denomination seemed to be the preference of the British authorities, education was still seen through a religious lens. Prior to 1831 schooling in Ireland like the rest of the United Kingdom was not heavily regulated and the curriculum could vary extremely, however as Coolahan (1981, p. 4) observed:

Ireland, as a colony could be used as an experimental milieu for social legislation which might not be tolerated in England where laissez-faire politico-economic policies were more rigid and doctrinaire.

And so, in 1831 the Chief Secretary of Ireland, Edward Stanley began the first major educational policy proposal in Ireland, for a multi-denominational (though not secular) educational system. This proposal would encourage both a multi-denominational management of schools and a multi-denominational student body. The National Board of Education would be made up of the Duke of Leinster, 2 members of the Church of Ireland, 2 members of the Catholic Church, and 2 dissenters – 1 Presbyterian and 1 Unitarian (Fleming, 2017, p. 203). The makeup of this Board demonstrates that the intent of this educational reform was not the secularisation of education, and indeed in the final draft of the letter that Stanley (1831) published he stated that the curriculum would provide for ‘combined moral and literary, and separate religious instruction’.

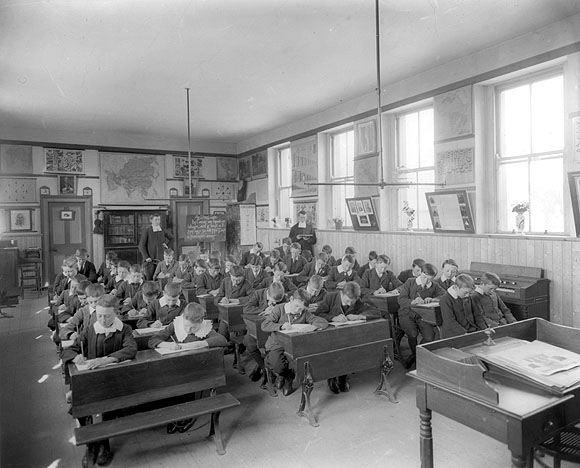

POOLEIMP 903 care of National Library of Ireland

This non-denominational nature of education in Ireland was summed up by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli when he wrote to then Chief Secretary Michael Hicks Beach (Walsh, 2022):

the Church . . . has educated England, and denominational education was a necessity. It is not so in Ireland: there, it is Parliament that has educated the people, & Parliament has decided against denominational education.

Despite this intention and belief, the management of individual schools in Ireland both primary and secondary remained largely denominational. Prior to the 1878 Intermediate Education Bill the nature of post-primary education was haphazard. The bill provided fees to schools and prizes to students following results from the public examinations (O’Donoghue, 1999, p. 20), but barring this with little interference from the state (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 26). The financial incentives of payments for results would lead to an examination focused curriculum that would show issues quite quickly. So much so that barely a decade later the Archbishop of Dublin William Walsh wrote in his Statement on the Grievances of Catholics in Education (1890):

If the Commissioners do not wish to see the Training Colleges degraded to the level of mere “grinding” and “cramming” institutions, they will have to make a total change in the character of their examinations.

The expansion of secondary schooling in the later portion of the 19th century, while modest in comparison to numbers in primary education and mostly drawing from the middle class, would also see an increase in the numbers of girls in post-primary education, in particular in subjects that were required for university courses such as Latin, Greek, and Mathematics. This was highlighted by the 1881 census and as argued by Ó hÓgartaigh (2009) was encouraged and facilitated by the expansion of convent schools. This was not a development that was universally embraced by the Catholic church with the bishop of Meath stating in 1883: ‘The advent of the new woman who demanded equal rights with her brother in admission to a study of the exact sciences and to the Pagan literature of Greece and Rome as well as to the realms of Law and Medicine and all the liberal professions.’ (Ó hÓgartaigh, 2009).

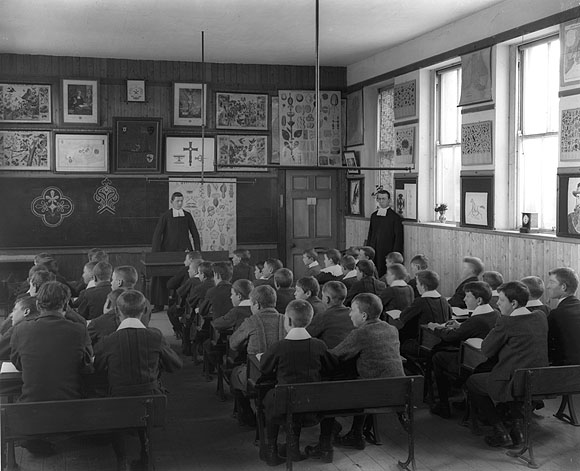

William Lawrence, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During the Irish Revolutionary Period the British Government through MacPhearson’s Education Bill (1919-1920) attempted to introduce a radical structural reform of the education system in Ireland, both in Ulster and in the rest of Ireland. This bill would have brought about a national education department, financing of schools through local taxation and local education committees (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 27). This was staunchly opposed by the Catholic Church with the Catholic Clerical School Managers stating that ‘the only satisfactory education system for Catholics … wherein Catholic children are taught in Catholic schools by Catholic teachers, under Catholic control’ (McManus, 2014, p. 16). The proposed bill did did not come to pass and with the end of the War of Independence in 1922 the new Irish Free State’s intervention into the education system focused on it as an avenue for revitalising Irish as a national language, working in cooperation with the Catholic Church (McManus, 2014, p. 20). The National Board of Education was folded, and its remit went to the new Ministry of Education with the Irish language being made compulsory for all students and all teachers to give at least some of their instruction through Irish (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 70). Though when the state proposed an intensification of Irish language education at the expense of English and Latin, they faced strong opposition from the Catholic hierarchy who felt that this would have a detrimental impact on the training of priests, and the state quickly reversed course (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 31) showing the strength of the Church and relative weakness of the government in educational policy during this early period of the Irish State.

The management of primary and voluntary secondary schools would be left, for the most part, to the various Church bodies, the Department of Education in its first annual report stated that it would assume no responsibility in appointing teachers, principals, or school managers (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 5). This policy would remain largely intact from the foundation of the state until 1967 (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 40). This relationship between church and state was satisfactory for the Church hierarchy with Rev. Timothy Corcoran, Professor of Education in UCD and a senior clerical spokesman on education stating that the relationship was a ‘model one’ (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 28). Even when the state did intervene in educational policy it was done with the Church as a partner. When the Vocational Education Act was implemented in 1930 just 7% of the population received a secondary education and the student body was still primarily drawn from the middle class, both Catholic and Protestant (Ó hÓgartaigh, 2009). Like the attempted McPherson Education Bill 1919-1920 the Vocational Education Colleges would be administered by ‘local authorities, supported by local rates’ (McManus, 2014, p. 49) and 38 were established. Though these were to be secular and non-denominational in nature, John O’Sullivan, the Minister of Education, took the concerns of the Catholic hierarchy regarding co-education of boys and girls into consideration and instructed the VECs to schedule their classes so boys and girls attended at different times. As well as this the secular nature of the VECs was curbed somewhat by the eligibility of priests to be appointed to the VECs boards and by the 1950s 22 of the 27 remaining VECs had priests as their chairmen (McManus, 2014, p. 50). The vocational schools also did not offer the Intermediate and Leaving Certificate examinations, as part of O’Sullivan’s assuaging of the concerns of the bishops (O’Donoghue, 1999, p. 103). This ensured the segregation of secular schooling from the general post primary system and the primacy of the denominational secondary schools and reinforced the view that it was a lesser form of education.

The removed nature of state involvement in education was solidified with the 1937 Constitution. Article 44 which dealt with states that the family is to be recognised by the state as ‘the primary and natural educator of the child’. This statement was used by the Catholic Church to argue that the state should not go against the wishes of parents, and that the Church should be in the position to advise parents on the education of their children on the grounds that it was working to protect the immortal soul of the child (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 144). And this protection of the soul and providing of instruction was not limited to management, but instruction as well with nearly 61% of teachers in the secondary school sector being clerics of some description, remaining at 54% by 1961 (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2022, p. 42).

By the middle of the 1960s the state began to take a more active role and change in its role in the education system. The Investment in Education report 1966 by the Department of Education and the OECD can be seen to represent a paradigm shift in Irish educational policy towards a ‘human capital’ model (O’Donoghue, 1999, p. 145). This economic conception of the purpose of education occurred as members of the Department of Education sought the modernising of education from a financial perspective, with then Assistant Secretary Sean O’Connor arguing for coeducational schools against the wishes of church authorities not for any developmental reasoning, but purely for efficiency (Iwashita, 2022). Coupled with this more proactive state the church hierarchy in Ireland needed to deal with the impact of the Second Vatican Council, where religious orders were in conflict over implementation of the changes, though the educational document of the Council, Gravissimum Educationis did emphasise the individual rights of parents in education (Nicolson, 2022) and so was in line with the policy and arguments of the Irish church authorities. This brought radical change to the structure of the Catholic Church and occurred alongside the Irish government becoming more active with regards to educational policy (O’Donoghue and Hartford, 2022, p. 191). As the state began to take on this role there was a scramble by church authorities to pivot in the new landscape, Future Involvement of Religious in Education (FIRE) report in 1973 represents a rapprochement between church authorities, the state and teachers’ unions (Delaney, 2021).

Religious character of schools continued to be considered important into the 1990s. In a reversal of the proposed 1997 Education Bill the Education Act 1998 defended the rights and power of patron bodies in schools (McManus, 2014, p. 313). This was the first part of a participatory and collaborative process of education reform, with Church educational bodies viewed as one partner of many alongside teaching unions and parents’ associations (Walsh, 2022). As with the Education Act other legislation from the same time would support the denominational structure of school bodies. The Employment Equalities Act 1998 and Equal Status Act 2000 had exceptions carved out for schools to give preferential employment or admission to teachers and students that are members of their religion or ethos (Rougier and Honohan, 2015).

This would remain the status quo until the Education (Admission to School) Act 2018 which amended the Education Act 1998, the Equalities Act 1998, the Equal Status Act 2000 and the Education (Welfare) Act 2000 with the main consequence being that schools could no longer prioritise baptised children in admissions policy. The financing and administration of school system in Ireland is highly centralised, but management mostly devolved to non-governmental bodies, either charitable or private (Rougier and Honohan, 2015) and despite these recent policy interventions by the state denominational, and in particular Catholic, ethos remains dominant for schools in Ireland. In 2021 88.6% of students were enrolled in a primary school with a Catholic ethos (Department of Education, 2022) and in 2020 50.1% of post-primary enrollments were in a school with a Catholic ethos (Department of Education, 2020).

The initial statement, on Irish education being a development between church initiatives and state intervention succinctly sums up the nature of the history of education in Ireland. The various church bodies viewed their role as the natural educators and safeguards of the welfare of children. The state, both under British administration and after independence, had sought to work with church bodies and it is only in the very recent history of the state that the denominational structure of the education system has been challenged in legislation. Although the trend is towards a non or multi-denominational ethos in schools a religious ethos still remains the lens through which the majority of children receive instruction.

Reference list

- Coolahan, H. (1981) Irish Education: It’s History and Structure. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

- Delaney, C. (2021) ‘’There Seems to Be Some Misunderstanding’: Church-State Relations and the Establishment of Carraroe Comprehensive, 1963-67’ Irish Educational Studies 42 (1) pp. 79-97.

- Department of Education (2020) Statistical Bulletin Enrolments September 2020 – Preliminary Results. Dublin: Statistics Section Department of Education.

- Department of Education (2022) Statistical Bulletin – July 2022 Overview of Education 2001 – 2021. Dublin: Statistics Section Department of Education.

- Education (Admissions to Schools) Act 2018, No. 14, Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- Fleming, B. (2017) Irish Education and Catholic Emancipation, 1791-1831. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Ireland (2018) The Irish Constitution. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/d5bd8c-constitution-of-ireland/ (Accessed: 30 March 2024).

- Iwashita, A (2022) ‘Denominationalism, Secularism, and Multiculturalism in Irish Policy and Media Discourse on Public School Education’ in B. Walsh (ed) Education Policy in Ireland Since 1922. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 87-116.

- McManus, A. (2014) Irish Education: The Ministerial Legacy, 1919-99. Dublin: The History Press.

- Nicolson, S. (2022) ‘Theology of Education in the Second Vatican Council’s Gravissimum Educationis’ Theology and Philosophy of Education 1 (1) pp. 32-39.

- O’Donoghue, T.A. and Harford, J. (2022) Piety and Privilege: Catholic secondary schooling in Ireland and the theocratic state, 1922-1967. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- O’Donoghue, T.A. (1999) The Catholic Church and the Secondary School Curriculum, 1922-1962. New York: Peter Lang.

- Ó hÓgartaigh, M. (2009) ‘A Quiet Revolution: Women and Second-Level Education in Ireland, 1878-1930’ New Hibernia Review 13 (2) pp. 36-51.

- Rougier, N., and Honohan, I. (2015) ‘Religion and education in Ireland: growing diversity – or losing faith in the system?’ Comparative Education 51(1) pp. 71–86.

- Stanley, 3. (1831), ‘a letter from the Chief Secretary for Ireland, to His Grace the Duke of Leinster, on the Formation of a Board of Commissioners for Education in Ireland.’ http://irishnationalschoolstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Stanley-letter-1831-Boards-Of-Management.pdf accessed 01 April 2024.

- Walsh, B. (2022) ‘More Sinn’d against than Sinning? The Intermediate System of Education in Ireland 1878-1922.’ History in Education 51 (3) pp. 381-400.

- Walsh, T. (2022) ‘Primary Curriculum Development in Ireland 1922-1999: From Partisanship to Partnership’ in B. Walsh (ed) Education Policy in Ireland Since 1922. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 11-35

- Walsh, W. (1890) Statement of the Chief Grievances of Irish Catholics in the Matter of Education. Dublin: Browne and Nolan.