When he blocked British entry into the European Economic Community for the second time in January 1963 Charles de Gaulle stated that:

England in effect is insular, she is maritime, she is linked through her exchanges, her markets, her supply lines to the most diverse and often the most distant countries; she pursues essentially industrial and commercial activities, and only slight agricultural ones. She has in all her doings very marked and very original habits and traditions. (Charles De Gaulle, Press Conference transcript 14th January 1963)

De Gaulle, who had repeatedly blocked attempts by the United Kingdom from joining the then European Economic Community, was strongly of the opinion that Britain was not a truly European nation and would never have the same interests at heart as the rest of Europe. To see how people felt about the UK as a European nation at the time of the referendum in 2016 I had a look at three articles published at the time. Two are the editorials published in the last days before the British public went to the polls for the EU referendum, while the third is from the Oxford University Politics blog by Jan Zielonka, Professor of Politics at Oxford University, whose piece ‘Brexit Referendum Folly’ argues that regardless of the outcome of the referendum there would be dire consequences for Britain and the rest of the European Union. The referendum on EU membership had the highest voter participation in any UK vote since 1992 (Fisher, 2016), and had very strong language and divisive arguments from both sides of the debate.

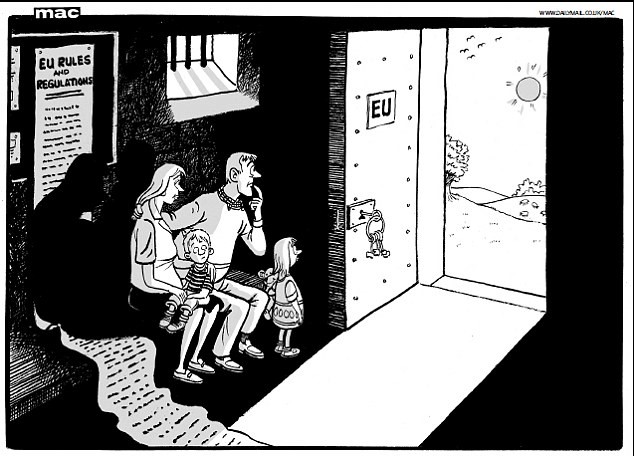

The first editorial is from the Daily Mail published on the 21st June 2016.. It is a very widely circulated paper, with a daily readership of 4,895,000 through print and online, outstripping every other daily paper barring The Sun (The National Readership Survey, 2016). 80% of their readership are over 35, and roughly 66% coming from ABC1 NRS social grades. Over 80% of the readership in Great Britain are living outside of the Greater London area and Scotland (Newsworks, 2016). The editor of the Mail, Paul Dacre is a man known for his strong anti-European views, and his ability to resonate with Middle England; as Peter Oborne says, ‘he articulates the dreams, fears and hopes of socially insecure members of the suburban middle class’ (Wilby, 2014). The thrust of the argument presented by the article is that the EU is dishonest and a servant to the global capitalist elites and not the citizenry, it allowed the rise of far-right movements throughout Europe, and that it infringes on the UK’s national sovereignty, while insidiously pushing for greater integration and federation of Europe as a whole. The piece uses striking visuals to support the text, such as the cartoon by their in-house cartoonist Mac, where a nice atomic family look out of the dank and dreary cell that is the European Union into the bright open expanse of freedom.

Of the three pieces I looked at the Mail‘s is the one that directly references statistics the most. While some of these figures are accurate, but leave out contextual information, which would make the figures less shocking and less likely to cause outrage. For example, The Mail asserts that only 3.6% of European Commission staff are British, the implication being that Britain has less influence over Commission policy than other members, and that between 40-50% of laws are dictated to the UK from Brussels. The first of these claims is very close to the truth, the actual percentage being 3.8% (European Commission, 2016). However, it does neglect to mention two relevant caveats to this; firstly, if all EU nations had equal representation in Commission staff they would each have just under 3.6%, and secondly that many other member states have even less representation, including France with only 2.4%. Representation at this level is heavily skewed by the large proportion of Belgian and Italy staff (18.5% and 10.6% respectively). The second claim is more insidious, as it misrepresents how European and national law interact; Vaughne Miller’s report for the Houses of Commons Library states that ‘there is no totally accurate, rational or useful way of calculating the percentage of national laws based on or influenced by the EU’, but estimates that 6.8% of primary legislation placed obligations on member states (House of Commons, 2010). The Mail also states that the EU lawmakers are not ‘accountable through the ballot box to the 500 million people they rule’ which is simply not true, as those who propose EU law are the members of the European Parliament: ‘The European Parliament is the EU’s law-making body. It is directly elected by EU voters every 5 years.’ (Europa, accessed 10th November 2016) Overall the article’s appeal is convincing, makes a clear case and (very important for referenda) makes an emotionally charged appeal.

The second piece is Jan Zielonka’s on the Oxford University Politics Blog is run by the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford, and sees itself as a ‘promote our academic research and commentary to readers in and outside the university’ (Oxford University Politics Blog, 2016). As a platform for the broadcasting of ideas and discussion it tries to take a neutral and measured stance, publishing articles from all sides of the debate, if they have academic merit. Zielonka is a professor of European Politics at Oxford University, and has written several articles and books on the European Union, and envisions it as a neomedieval empire, an entity wholly unlike the traditional idea of the state (Venneri, 2008). He is writing for an academic audience, and one that is interested in the advancement of democracy in the world, the article having been originally published on openDemocracy. In his piece, ‘Brexit Referendum Folly’, he heavily criticises both the Labour and Conservative Remain campaigners for the ‘perverse’ arguments they made in favour of Remain. He states that none of the leadership on the Remain campaign have a genuine support for the European Union, arguments they put forward in favour of Remaining in the EU, in Zielonka’s view David Cameron’s argument for remaining in the EU is that the EU has minimal impact on the UK politically, as they are not participants in key aspects of the European project, Schengen and the Eurozone, meanwhile Jeremy Corbyn disagrees with the EU as an organisation, but that leaving the EU would lead to greater influence of neoliberalism. Zielonka suggests that these arguments one weak and counterintuitive, the other pragmatic and entirely political, aren’t the type to sway voters on such an emotive issue. ‘A referendum forces politicians to present complicated issues in simplistic black and white terms, which obviously rewards populist politics and demagoguery.’

He goes on to state that that the referendum was called at all, regardless of result, would have a negative impact on the European Union. Strong invective among the British stronger anger about the EU, and the referendum’s very existence gives legitimacy and hope to eurosceptics in other member states. The leaders of the European Union do not escape from Zielonka’s criticism in this piece, with Jean-Claude Junker being singled out for his role in undermining confidence in the EU’s institutions, and the laisse-faire attitude in Brussels in the face of increasing Euroscepticism. The power of the European Parliament has been increased with successive treaties, but with very little interest among the electorate, average EU turnout for the 2014 election being only 42.6% (European Parliament, 2014). Zielonka argues that with a disconnect between the centre of EU decision making and the nations that make up its members, a serious rethinking is need of how the EU will continue to function while ‘technocrats dominate policy-making while populists dominate politics.’

The final piece I looked at was The Guardian’s editorial from the 20th June 2016, titled ‘The Guardian view on the EU referendum: keep connected and inclusive, not angry and isolated’. Guardian circulation reaches 2,242,000 daily print and online readers (National Readership Survey, 2016), 79% of which are from the ABC1 NRS social grades, with 70% being over 35 years old, and about 30% of their readership in Great Britain coming from the Greater London area and Scotland (Newsworks, 2016). As with The Daily Mail, The Guardian is writing for a middle-class audience. The focus of The Guardian’s editorial is a critique of the arguments and claims made by the Leave campaign leading up to the referendum, and a warning for the dire consequences of leaving the EU. It asks the reader, is leaving the EU worth the potential for a resurgence in the Scottish national movements, or renewed violence in Northern Ireland?

The argument that the ability to deal with climate change and carbon emissions is stronger within the EU would appeal to The Guardian’s core readership, but would do little to sway those who The Guardian needed to appeal to, whose concerns are more focused on their own immediate. ‘Those who vote to leave as a protest against the elite will, in truth, be handing the keys to the very worst of that very elite,’ is the clarion call, but that is not enough. The article states that, at its heart, the UK is a European nation, in terms of historical and cultural links. This is a view that is not shared by the clear majority of Britons, and as Jan Zielonka has argued, even the leadership of the Remain campaign. An appeal to the European ideal, while still assuring the reader that ‘Britain is not part of the eurozone, and the EU is not a plot against the nation state’ is a bizarre argument to make. It does concede that the EU is imperfect, but argues that staying within and reforming the EU is a better solution than leaving and striking out alone into the world. This style of argument had worked in the Scottish independence referendum on 2014, so would not an unreasonable one to make, if the British public did see themselves as European in a similar way to how they see themselves as British. But the closing statement invokes the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox, as a warning against hatred and fear, and claims that ‘the EU is not just the least bad option’, but the arguments The Guardian brings to bear do not convince of this.

(NB: This is something I originally wrote back in November 2016 but did not publish, I’ve edited it lightly, but have not overhauled it too much as its object was an examination of the discourse at the time of the referendum, and not of it now, two and a half years later.)

Bibliography

The Daily Mail Comment. (2016), ‘If you believe in Britain, vote Leave. Lies, greedy elites and a divided, dying Europe – why we could have a great future outside a broken EU’ The Daily Mail 21 June. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-3653385/Lies-greedy-elites-divided-dying-Europe-Britain-great-future-outside-broken-EU.html [Accessed 31 October 2016].

De Gaulle, Charles. (1963) ‘Press conference given by General de Gaulle (14 January 1963)’ transcript. Available at: http://www.fransamaltingvongeusau.com/documents/cw/CH2/7.pdf [Accessed 31 October 2016].

The Editorial Staff. (2016), ‘The Guardian view on the EU referendum’ The Guardian 20 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/20/the-guardian-view-on-the-eu-referendum-keep-connected-and-inclusive-not-angry-and-isolated [Accessed 6 October 2016].

Europa. European Parliament. Available at: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/european-parliament_en [10 November 2016].

European Commission. (2016) Cadenza Document Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/civil_service/docs/europa_sp2_bs_nat_x_grade_en.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2016].

European Parliament. (2014) Results of the 2014 European Parliament Elections. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/elections2014-results/en/election-results-2014.html [Accessed 10 November 2016].

Fisher, Stephen (2016). ‘Why did the UK vote to leave the European Union?’ The Oxford University Politics Blog, 25 June. Available at: http://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/uk-vote-leave-european-union/ [Accessed 5 November 2016].

House of Commons (2010) ‘How much legislation comes from Europe?’ Commons Briefing papers RP10-62 London: House of Commons Library. Available at: http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/RP10-62#fullreport [Accessed 11 November 2016].

The National Readership Survey. (2016) NRS Jul15-Jun16 fused with comScore Jun2016. Available at: http://www.nrs.co.uk/downloads/padd-files/pdf/nrs_padd_jul15_jun16_newsbrands.pdf [Accessed 6 October 2016].

Newsworks. (2016) The Daily Mail. Available at: http://www.newsworks.org.uk/Daily-Mail [Accessed 12 November 2016].

Newsworks. (2016) The Guardian. Available at: http://www.newsworks.org.uk/The-Guardian [Accessed 12 November 2016].

The Oxford Politics Blog. About. Available at: http://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/about/ [Accessed 4 October 2016].

Venneri, G. (2008) ‘Back from Westphalia’, The Review of Politics, 70 (1), pp. 110–113.

Wibly, P. (2014), ‘Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain’ New Statesman 2 January. Available at: http://www.newstatesman.com/media/2013/12/man-who-hates-liberal-britain [Accessed 6 October 2016].

Zielonka, Jan (2016). ‘Brexit Referendum Folly’ Oxford University Politics Blog, 4 June. Available at: http://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/brexit-referendum-folly/ [Accessed 5 November 2016].